There are certain extinct animals that never seem to die in the minds of the public – the woolly mammoth and the dodo are two prime examples.

Another is the passenger pigeon – interestingly a cousin of the dodo, both being members of the Columbidae family.

The passenger pigeon was endemic to North America. At one time there was a huge population but they became extinct in the early twentieth century.

Origins of the Passenger Pigeon

The passenger pigeon was native to the North American continent.

For a long time, science believed the passenger pigeon to have descended from pigeons and doves in the Zenaida genus that had colonized the great plains but later studies of its taxonomy and ecology suggest it is more closely linked to migratory Columbidae crossing the Pacific from South East Asia or from Beringia (an area that now corresponds to an area spanning Alaska and parts of Russia and Canada).

Early explorers and settlers very frequently mentioned the species in their writings, with Samuel de Champlain reporting ‘countless numbers’ of them in 1605.

At the healthiest stage of their existence, it is estimated the passenger pigeon represented between 25 and 40 percent of the total bird population across the United States. At the time that the Europeans set foot on American soil, there were between 3 billion and 5 billion passenger pigeons in the country.

Population numbers really are incredulous but they come from such revered sources that they are also totally believable.

Kevin Johnson, an ornithologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey at the University of Illinois, has stated that in the early 1800s, the passenger pigeon was the most abundant bird species on the planet.

Two doyens of scientific ornithology in the USA both made statements.

John James Audubon claimed he watched a flock of 300 million pigeons pass overhead for three days, while Alexander Wilson estimated one particular flock contained two billion birds.

It is also said that nesting colonies could cover areas of several miles wide and forty miles long and produce so much pigeon poop it could kill areas of forest.

Reports say poop could be as 1 foot deep!

One report put a large nesting site in Wisconsin as covering 850 square miles with the number of birds in the colony estimated at 136 million.

American writer Christopher Cokinos suggested that if all the passenger pigeons in the USA at one time birds flew in single file, they would have stretched around the earth 22 times.

The common name of this bird derives from the French word passager which means ‘passing by’, and it fits this bird perfectly thanks to its migratory habits.

The scientific name of the species – Ectopistes migratorius – also refers to its famous migratory characteristics.

For a very long time, it was thought that the mourning dove was the closest relative to the passenger pigeon and at times the two were often confused because of their similar morphology.

More recent research, however, has suggested that the closest genus to the passenger pigeon are members of the Patagioenas genus like the band-tailed pigeon and the white-crowned pigeon.

Distribution And Habitat of the Passenger Pigeon

The passenger pigeon was found across the majority of North America: east of the Rocky Mountains, from the Great Plains all the way to the Atlantic Coast.

It was also abundant in the south of Canada in the north and east of the Mississippi in the south.

The preferred habitat of the passenger pigeon was great expanses of hardwood forest.

The main nesting area stretched from the Great Lakes to New York and northern birds migrated south for winter.

Migrations, mostly in March and April could be as far from Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia to Texas, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia and northern Florida.

Sightings of passenger pigeons were reported in some western states, Bermuda, Mexico and Cuba during harsh winters.

It is known that while it’s mostly agreed that the pigeon did not readily inhabit the far western US states, they did at some period in early history because, among the 130 passenger pigeon fossils found, there were specimens recovered from La Brea Tar Pits in California.

Status of the Passenger Pigeon

In 1895 the last nest and egg of that species to be found in the wild were collected near Minneapolis, although the exact location is unknown.

The last known confirmed wild specimen was reportedly shot in 1899 in Babcock Wisconsin.

The passenger pigeon officially went extinct on September 1, 1914, when Martha, a resident of Cincinnati Zoo passed away. Martha had been gifted to the zoo by Charles Whitman of the University of Chicago.

She became the last known individual after her two male companions passed away in 1910.

Martha lived to the age of 29 and is now on display in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C.

The American Ornithologists’ Union offered $1,500 between 1909 and 1912 to anyone finding a nest or nesting colony of passenger pigeons, but the effort was futile.

How the Passenger Pigeon Became Extinct

By the early 1900s, despite a typical lifespan of 15 years, there were no wild passenger pigeons left because of hunting and deforestation.

Due to their massive numbers, pigeons were hunted on a huge scale. Pigeon meat was easily obtainable and cheap.

Sometimes, pigeon hunting wasn’t even necessary. Anecdotal evidence states that during the nesting seasons, it was possible to simply wander into a colony and pick up squabs from the ground where they had fallen from or knocked out of their nests.

They were also hunted though and in great numbers. Hunters had numerous methods of getting the birds and they caused mass disruption to the colonies, resulting in wholesale nest abandonment and reduced breeding success.

Although laws were passed in various states to try to provide some protection for the passenger pigeon population, they were ignored.

The advent of the railways brought a new threat. Forests from the Mid-West to the West Coast were cleared for laying tracks. Many millions of passenger pigeons were shipped eastwards but deforestation for agriculture and the American Civil War had already devastated the natural habitat.

It is known that a single hunter shipped three million pigeons east from Michigan in 1878. In 1889, it was declared the passenger pigeon was extinct in that state.

This is an example that drives home how rapidly the extinction of this species came about.

Many have tried to answer why the passenger pigeon was not able to survive given that there was still suitable habitat after market hunting became harder and less profitable.

The most accepted theory is that they needed to be able to form vast colonies to survive. This enabled them to “crowd out” predators reducing the loss of nesting birds. With less habitat, enormous colonies were not as easy to form.

The true reason for the extinction of the passenger pigeon remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of nature (except we know that human intervention played a major part!)

Sadly, the passenger pigeon’s nearest relative, the white-crowned pigeon, is also classed as Near Threatened on the ICUN Red List.

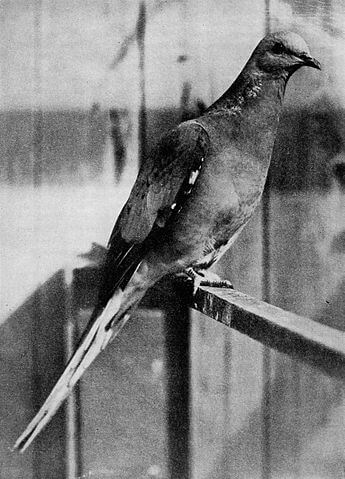

Appearance of the Passenger Pigeon

| Wingspan | Length | Weight | Coloring | |

| Passenger Pigeon | 56 – 62 cm | 38 – 42 cm | 450 – 510g | Blue-grey with black streaks, pink breast |

| Average Feral Pigeon | 64 – 72 cm | 32 – 37 cm | 300 – 500 g | Bluish grey with some black |

The passenger pigeon was slightly larger but more streamlined overall than the feral pigeon.

This bird is morphologically commensurate with its flight characteristics of grace, speed, and maneuverability.

The passenger pigeon had a small head and neck, with a long, wedge-shaped tail and wings that were long and pointed. These wings were powered by large breast muscles that provided the capability for strong and prolonged flight.

The head and upper portions of the male passenger pigeon was a clear, blue-gray color with added black streaks on the scapular and wing coverts.

There were patches of iridescent feathers in shades of metallic bronze, green and purple on the neck and upper mantle.

The breast and lower throat were a soft rose color that gradually shaded to white.

The tail had two brownish-grey feathers longer than the others and the rest was white.

The passenger pigeon had bright coral-red feet and legs, a black bill and a deep purplish-red iris.

In females, the overall coloring was much paler and duller. Head and back were a brown-gray, with the iridescent patches on the throat and back of the neck being less bright than in the male. The breast was pale cinnamon.

The Character Of The Passenger Pigeon

The passenger pigeon was known for being an incredibly social bird living in huge colonies, especially during the breeding season.

They would roost in such huge numbers that they would frequently pile in on each other’s backs.

Roosting was in a slumped position which hid their feet and when they slept, the would rest their bills on their breast buried in the feathers.

The passenger pigeon is reported as rarely ever being aggressive or fighting.

It had a strong flying ability and was estimated to be able to average speeds of 100kmh during the peak phases of its migration.

The passenger pigeon flew using quick, repeated flaps of the wings that increased its velocity. It was equally as adept at flying quickly through dense forest as it was flying through vast open spaces.

Reports of the passenger pigeon’s vocalizations describe them as being deafening when in flocks, audible for miles.

The individual voice was loud, harsh and lacking melody.

Connected sounds did not produce a song but rather a collection of coos, clucks and twitters.

They made bell-like sounds during mating and nest building was accompanied by croaking noises.

Like all pigeons, they made alarm calls when a threat was detected.

Diet of the Passenger Pigeon

The diet of the passenger pigeon varied and changed depending on the seasons.

In the fall, winter and spring months, the diet mainly consisted of things like acorns, beechnuts and chestnuts, while during the summer there was a range of soft fruits and berries available also.

On occasion, passenger pigeons would also eat snails, worms, caterpillars and other small invertebrates, particularly while breeding.

The passenger pigeon had a very large crop to store food. It could swell to the size of an orange and able to hold 15-18 acorns!

It is estimated a typical pigeon would consume 100g of food each day.

The bird apparently had a taste for salt which it obtained from brackish water or salty soil.

Water was drunk at least once a day, most usually at dawn. Birds would perch on top of each other to drink.

Passenger Pigeon Mating And Breeding

The passenger pigeon was a communally breeding species.

It isn’t certain how many times a year the passenger pigeon bred, but the most common assumption is once per year.

The nesting period would last anywhere from four to six weeks, and the flock would arrive at its chosen nesting ground in March in southern latitudes, and a little later in the north.

The species did not appear to have any kind of site fidelity, often choosing to nest in a completely different location from year to year.

The passenger pigeon had a courtship ritual that took place on a branch,

The male flourished his wings while making a “keck” sound then gripped the branch to vigorously flap his wings up and down.

When the female came close, he pressed against her with his head held high. The female pressed back and if they signaled agreement to mate, they undertook preening of each other.

After preening, they “kiss” and then copulate.

Nest building began immediately afterward. The female chose the nesting site on a strong branch, the male collected the materials and the female constructed the nest.

The nest was built at least 2 meters off the ground (up to 20 meters) of 70-150 twigs in a loose bowl-like construction.

One or two white, oval eggs were laid and were incubated by both parents for 12 to 14 days.

Both parents fed the baby crop milk which grows rapidly. After two weeks it can weigh as much as its parents.

The parents abandon the baby 14 to 16 days after hatching, leaving it to fledge alone.

The nesting cycle takes 30 days.

Care Of the Passenger Pigeon

As the passenger pigeon has been officially extinct for more than 100 years, we think it is safe to say that there are no care instructions to follow for this particular species!

This may change in the near future if recent reports of sightings of the passenger pigeon are verified.